Special Story of Višegrad

They killed all her sons. She knew that a return to Višegrad was never going to happen, yet she never uttered a single word of hatred.

The parade of Chetniks in Višegrad recalls 1992 memories from this city.

When in the night of May 1992 in the place of Stupe in Višegrad, they took away my uncle Muhamed who wore only pajamas to the police station for an interrogation, it seemed to me then that the whole world is slowly falling apart and that it could not get much worse than the picture my aunt took was showing. The picture was taken when she succeeded in an attempt to get him a pack of cigarettes, but she couldn’t recognize him due to the beating he suffered the previous night.

It equally hurt that their best man from the wedding Boro, who she asked for help, did not know of them since that night. Well, someone said long time ago that it can always get worse.

In only ten days all the Muslims of Višegrad were called to join the convoy. Men, women and children were piled up in eight busses and seven trucks and they were told: “Turks, go to your own!”

In one of those was my younger uncle Muharem, who would be separated from his mother (my grandmother), his spouse, eight-year old daughter, and son. There were more close relatives, but the grandma remembered his chin the most; the chin that trembled and shook as they were taking him away with the rest of the men who they had taken all the money from previously.

Soon after I will come to realize that the eight-year suspense that followed, during which we waited to find out what really happened, was even more unjust. The State never offered any answer at all, and the stay in the Sarajevo under siege prevented us from getting any information on their destiny.

The greatest injustice

The lies that they were still alive felt good at moments; the lies that they were imprisoned in camps somewhere in Serbia were such information that kept alive my mother, grandma, aunts and their children.

And then, more just seemed to know what happened to them, whether they were dead, whether they were killed immediately or after the torture, whether they left any message, were they hungry, thirsty and barefooted before they were executed.

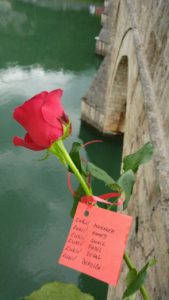

The fact that you could not see their dead bodies, that you could not bury them and say farewell the way your tradition taught you, was more painful and unjust than the deaths of those dearest ones in Sarajevo, because we could collect at least their bones to one place and have an opportunity to go and visit their mazars (graves), even those were in the park, to say our El-Fatiha prayers, leave a rose, light a candle or a cigarette, whatever one felt like.

And then, after death the greatest justice for my family was to find my uncles’ bones and remains.

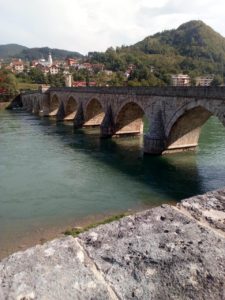

Visiting mass grave after mass grave is what followed then. Feelings were mixed there. For a moment you were happy for not finding their remains there, for then the hope remained that they would appear from nowhere, and then again you would fall in despair for not knowing how to behave, whether you should say your El-Fatiha prayers, deliver your rachmet before their souls, or throw a rose into the Drina river. Every single positive identification of a victim brought hope and later would leave us in a pit of sorrow from which we had to recover until some new information arrived.

We found Muharem eight years later in Paklenik, a mass grave near Sokolac. It hadn’t been dug over so we had no problem with the identification, as it was the case with Muhamed, whose body the Drina river threw out so the process of the identification was more difficult since people of Žepa caught only a part of his body so the bones spread out all over the place.

What an irony of life for us to find Muharem’s twenty meters deep mass grave dearer to us because it didn’t let the bodies to completely rotten out. It hadn’t been dug over either so it meant a lot to us that the bones were all in one place.

What an irony for us to feel glad that someone saw their killing, the N.N. witness from Hague. Our right to know the truth about their deaths drove us to madness, yet we wanted to hear it.

The thick wire around their wrists, kilometers of walk through thick forests, the final stop near the twenty meter deep pit, shot in the back of the head and then the push into the pit of the sinister name of Propast (the Doom). There were over 50 of them from Gornji and Donji Dubovik, Velatovo, Žagri, Smriječa, Župa and Dobrun.

They tried to hide their execution so they threw rocks, animal bones and animal corpses on top of their bodies.

The N.N. witness was at the end of the column of those who waited for their own death: he managed to break away from the column, and the thick trees guarded him from the few criminals who were there to execute the crime. The Serb women kept him hidden and they helped him to transfer to “his own”.

We found documents, small mirror and a small comb with Muharem. I recognized his track suit which hadn’t rotted, and as I was climbing down the small ladders additionally secured with a rope around my waist, I felt excited.

The thoughts were stronger than the reality I was seeing, so for the moment I remembered the joy ride in Okrugla, the basket I sat in and the rope my uncle held while pushing me away from him, throwing me up in heights laughing to my happy screams, because we always celebrated my birthday too on the 4th of July.

I climbed down into the pit with a smile on my face. I believed that his soul would recognize me and that it would make him sad to see me scared.

The final rest

I wondered how only the feeling lead me to his skeleton, even the forensics lady, the Polish lady from Iceland Elvira Eva Klonovski, believed that it could be placed in a lower of part of the cold and dark pit. Somebody made a comment that the bodies were hitting rocks as they were falling down. But I didn’t want to listen to the details.

Later I tried to make a story with the witness who survived, but quickly gave up. I heard that he was haunted by the feeling of guilt; he regretted for not having been killed with the rest of his country mates, with whom he lived, worked, went to school and grew up together.

After that we soon find Muhamed too. We felt a bit happier because he was buried in the Harem (Muslim graveyard near the mosque) in Višegrad. And then one day we receive a phone call from the Commission for the missing persons. They say they have to do an autopsy since a lady showed up claiming that it was not our uncle but her husband. But we have been to that mazar several times already, we brought flowers, and faced horrible secrets that city kept hidden.

What gives the right to someone to disturb him again, to take his bones out now? It was both just and unjust to go through this process again. Just to this lady who will finally find her husband in our uncles mazar and unjust to us who again had to go through the same search process.

When their bones finally found their rest and when we succeeded at identifying Muhamed too and bury him in the Vlakovo graveyard, very close to Muharem and the rest of the cousins and neighbors, my grandma said that she now could finally die at peace.

She didn’t wait to see the final sentence to Lukić who was sentenced by the county court in Belgrade to 20 years in prison, for the murder of 16 Bosniaks in the village of Mioče, Rudo municipality. The Hague also is leading procedures for the murder of other 84 Bosniaks from Višegrad.

She didn’t wait to see the sentence to Vasiljević (15 years), nor Tanasković (12 years, 8 years after appeal), nor any apology neither from Dačić nor Nikolić, nor did she have any need to publicly speak about what happened to her.

She only asked for decent burial for her sons, nice memories of them and nothing else. If I thought that grandma’s silence was indeed the result of her pain, I soon came to realize the message she carried along in her silence all the way.

Her form of fight was stronger than the hundreds of speeches about the genocide and holocaust. The silence of hers transformed us.

We were victims, but we never allowed to ourselves to feel like one. Not a single word of hatred ever came from her mouth. Not a single classification on theirs and ours was there. Even then when our cousin’s father and brother-in-law from Belgrade came to visit us for the first time.

While the NATO was bombarding Belgrade they somehow made it to Sarajevo to see our mutual princess, Lidija, who at the age of 8 fought with life.

My close ones, who were in the tranches around here, wished to share their experience with the people who, of course, came on a completely different occasion, but the post-war syndrome was stronger than the politeness. But everything about it was so fresh still.

I was truly impressed by the grandma’s reaction – she made the whole bickering stop and ordered to all of us to purchase a black shirt to our friend Serbian guy from Valjevo for him to, in a dignified manner, say final goodbye to his granddaughter and her grand granddaughter who in the mean time had lost her life.

She never saw us cry

There was something so sacred in that woman that never let us dare cry in front of her, nor complain, nor say how life hurts. We never dared curse anyone, neither those who committed the crimes nor those who traded with weapons at the beginning of the war. We cursed not those who made the innocent Bosniaks civilians return from Goražde to the occupied city, nor those who did not hold remembrance of the anniversary of their deaths and struggles, but won the elections thanks to them; not even those who never legally prosecuted those responsible.

Our sorrow became such a close part of us that it became inappropriate to share it with others. And my grandmother, mother of two murdered sons, never stopped rising from her seat to meet every single guest, for the purpose of, as she said, their good and happiness. She never stopped blessing both those known and the unknown, she never stopped gathering us around herself and never stopped asking God for a better world. She always had a bundle of fresh gurabijas (Bosnian cookies) in her drawer, in the case a Musafir (wayfarer) knocked on the door and she could surprise him.

She safe-guarded her šamija (Bosnian headscarf) as a nick of her eye and her dimijas (Bosnian ladies garment) could not be replaced by no dress, not even by those people brought to her from Hajj.

I don’t know if you ever had grandmas like this, but mine left such a huge mark on me, such a strong mark that while writing this text I start to look to myself a bit Malik-like, the character from the movie of Otac na službenom putu (When Father Was Away on Business). I moonwalk in a desire to see that beautiful face which sometimes long ago froze in time, the sky-blue eyes that always left the message of us being one and that the earthly justice is unreachable.

She always knew that the return to Višegrad was never going to happen and that she would find her final rest in Sarajevo, in the cemetery where her sons and grandchildren are. She was connected to the Šeher just like she was with Višegrad, and the Užice where the Zukić family finds their roots.

Her death anniversary is getting closer. I know that she never liked those mortuaries in the newspapers and it really made her angry when ladies would talk to each other while the Qur’an was recited during the Tawhid ceremonies. But, she loved when my texts were read to her so I dared to write one that will carry her message of peace.

Translated by Dženan Borovac

29 February 2016

Source: Al Jazeera

The preceding text is copyright of the author and/or translator and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.